Approximately 550 kilometres west of Dubbo, along the Darling River, lies the isolated desert town of Wilcannia in western New South Wales. It is home to the Barkindji people, one of Australia’s First Nations groups, and has a population of around 745. Despite the town’s tiny size and isolated location, which have led to serious issues with social fairness, public safety, and health, the town’s Aboriginal legacy is intricately intertwined into the environment and culture.

Although these designations need context, Wilcannia has developed a reputation throughout the years for being “dangerous” or fragile. The town has a number of intricate structural issues, such as high rates of certain types of crime, alcohol abuse, overcrowding, public health risks, and restricted access to basic services. However, its citizens exhibit tenacity, togetherness within the community, and a dedication to cultural preservation that resists easy categorisation.

Historical Background & Demographics

Over 60% of Wilcannia’s population identifies as Indigenous, according to census statistics. Despite the effects of colonialism and contemporary economic marginalisation, the Barkindji people have continued to live beside the Darling River for many generations, preserving their traditional customs and traditions. The Athenaeum and ancient storehouses are examples of the town’s historic architecture from its development as a river port in the 19th century. Even though infrastructure investment and economic prospects are far behind those in metropolitan areas, it is nonetheless a focus for cultural heritage today.

Public Safety & Crime

The crime profile of Wilcannia is higher than that of many other western New South Wales municipalities. Residents deal with high rates of domestic violence, property crime, and court procedural violations, despite the fact that there have been no recent killings reported. Instead of widespread anarchy, the total crime rate is around 60,000 incidences per 100,000 people, indicating socioeconomic stresses. These figures are a result of poverty, overcrowding in housing, and a lack of police presence.

Reports from travellers provide a complex viewpoint. Grey Nomads and long-distance travellers often say they feel secure during the day, particularly when they use approved caravan sites or designated pauses. “I have been through the town several times in recent years and it’s always seemed safe to me,” one tourist said. Others were wary, calling the village eerie at night with boarded-up buildings and closed gates. These incidents highlight the fact that, rather than a direct criminal threat, perceptions of risk are often shaped by Wilcannia’s distant location and obvious indicators of socioeconomic poverty.

In the town, alcohol misuse continues to be a major cause of crime, especially domestic conflicts and disruptions in public. High levels of consumption continue despite limits put in place by authorities, which has an impact on social cohesion and public safety. Social vulnerability is increased when substance misuse, economic hardship, and overcrowding are coupled.

Housing and Socioeconomic Disadvantage

Wilcannia has significant socioeconomic difficulties. Housing is nevertheless congested and of poor quality, and many people are unemployed and dependent on aid. Three bedrooms in a typical household may house 8–14 people, which makes illness management more difficult and adds to family stress.

Of the 220 residences in the community, 62 are owned by the Wilcannia Aboriginal Land Council, while the remaining 28 are owned by the Aboriginal Housing Office. Since 2000, when a number of residences were destroyed and rebuilt, a large portion of the housing stock has not received significant upkeep or investment. Continued neglect was highlighted by the unmet promises of new homes in April 2021. Overcrowding, poor upkeep, and a lack of new housing all contribute to a persistent vulnerability in social stability and public health.

The Delta Outbreak of COVID-19

Several of Wilcannia’s structural flaws were exposed and made worse by the COVID-19 epidemic. When the Delta version first appeared in the community in mid-August 2021, it swiftly infected around one in seven locals. The danger was increased by Indigenous residents’ low immunisation rates. Only 8% of people were completely vaccinated and fewer than 20% had gotten their first dose at the time of the first illness. These rates increased over the next several weeks, reaching 57% for first doses and 19% for complete vaccinations among Indigenous communities in far-western NSW.

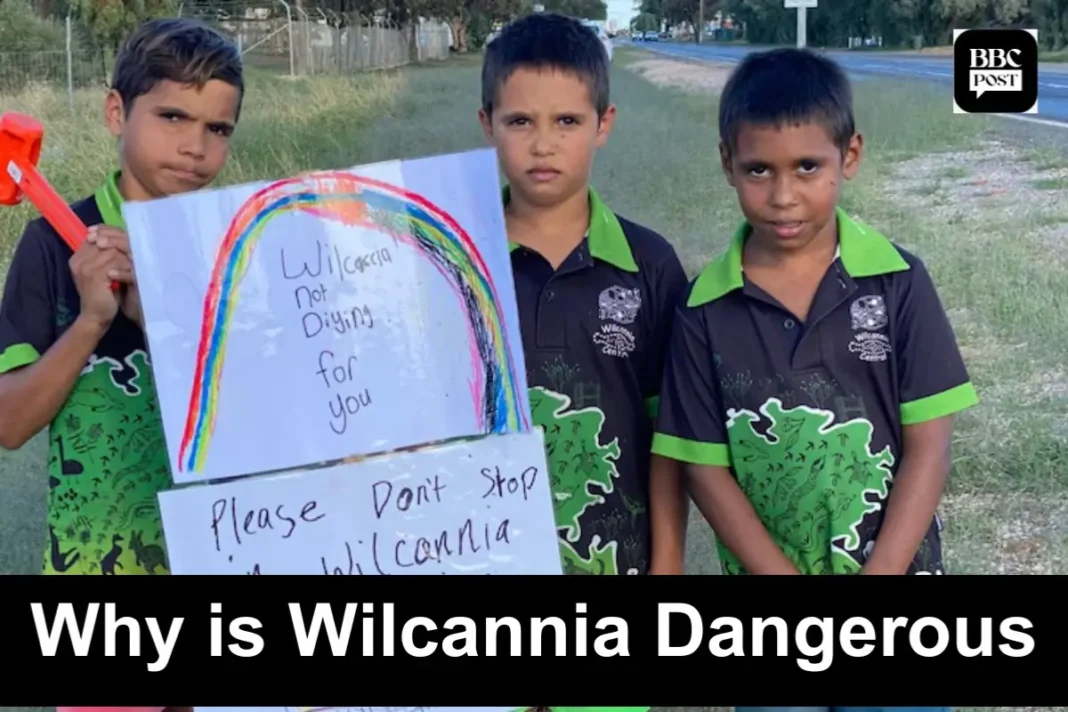

Preparations fell short in March 2020, despite early warnings from Aboriginal health agencies, including letters to the federal government. The town had put up banners that stated, “It is too dangerous to stop in Wilcannia,” indicating that the locals were worried about the possibility of the virus spreading. Isolation was almost impossible due to overcrowding, and several families were compelled to sleep outside or in tents. The epidemic brought to light long-standing disparities in access to resources, housing, and healthcare.

State health officials provided mobile homes and a caravan convoy as part of the emergency response, while the Australian Defence Force helped with logistics and food delivery. These actions were costly, expected to cost hundreds of thousands of dollars per month, and they were more of a short-term fix than a long-term one.

Resilience & Community Response

The effect of the epidemic was lessened thanks in large part to the local community. Food packs were sent to those who were being isolated by young locals like Katrina Hunter, who called the situation “scary and frustrating” and pointed out that city dwellers often had access to considerably more resources. Families unable to reach the town’s tiny store, which had sold out during lockdown, received kangaroo meat from hunters like Leroy Johnson. In the face of government failings, these gestures of communal cooperation showed resourcefulness and fortitude.

After decades of neglect, Jenny Thwaites, CEO of the Wilcannia Aboriginal Land Council, said, “Wilcannia has been neglected. I believe that if Wilcannia just vanished off the face of the planet, [the government] would be pleased. However, they won’t abandon their conventional dwellings. Her comments emphasise the community’s will to preserve its ties to place and culture while also expressing the anguish that many locals feel due to institutional neglect.

Local health groups and community leaders collaborated to manage logistics for food and shelter, encourage immunisation, and provide culturally relevant health advice. Despite funding limitations, these initiatives show a strong dedication to community well-being and resiliency in the face of structural disadvantage.

Health Disparities

In addition to COVID-19, Wilcannia has serious health inequalities. Chronic diseases including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory disorders are common, and life expectancy is lower than the national average, especially among Indigenous males. These issues are made worse by poverty, overcrowding, and limited access to medical care. According to public health experts, the Delta epidemic was a consequence of long-standing societal injustices, including decades of underinvestment in housing, infrastructure, and healthcare.

Views and Insights of Travellers

Wilcannia is often seen by tourists as a town of contrasts. The town is typically regarded as safe throughout the day and while remaining at designated stops. Travelling at night or making unattended pauses might be difficult because of social inferiority and isolation. Accounts from travellers show that rather than constant risks of crime, perceptions of danger are often impacted by infrastructure, isolation, and unfamiliarity with local circumstances.

Although there aren’t many facilities, Grey Nomads and other long-distance visitors observe that the town provides necessities like gasoline and basic supplies. Although Wilcannia’s image has sometimes been exaggerated in public discourse, the difficulties that locals especially Indigenous families face are real and persistent.

Conclusion

The narrative of Wilcannia is one of contrasts: the town is characterised by structural and historical deprivation, high rates of crime in certain categories, cramped housing, and susceptibility to public health emergencies. However, it is also a site of great cultural strength, communal initiative, and perseverance. Despite decades of neglect and structural injustice, the Barkindji people, local leaders, and volunteers are nevertheless able to maintain their town.

A thorough understanding of Wilcannia is necessary, acknowledging the human and cultural resilience that endures in this isolated area as well as the social, health, and safety issues. The town’s experiences with crime, COVID-19, and socioeconomic hardship highlight the ability of its citizens to adapt, band together, and support one another during times of crisis while also reflecting larger trends affecting rural and Indigenous communities throughout Australia.

FAQs

Is it safe to visit Wilcannia?

Wilcannia can be safely visited during the day, especially when staying in authorised caravan parks or official stops. Nighttime or isolated stops require caution due to remoteness, limited infrastructure, and social challenges. Travellers are advised to remain aware of surroundings and respect local culture.

What is the roughest town in NSW?

While several towns in western NSW face social and economic challenges, Wilcannia is often cited as one of the more disadvantaged towns due to elevated crime rates in certain categories, alcohol-related incidents, and socioeconomic vulnerability. Other towns, such as Bourke and Walgett, also report high domestic violence rates.

Is the Australian outback dangerous for tourists?

The outback presents natural hazards rather than crime. Extreme heat, long distances between services, limited mobile coverage, and wildlife risks are the main concerns. Tourists should plan ahead, carry sufficient supplies, inform someone of their travel plans, and avoid isolated areas at night.

How many Aboriginals live in Wilcannia?

Approximately 61–62 per cent of Wilcannia’s population identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. Most belong to the Barkindji nation, who have historically lived along the Darling River and maintain strong cultural ties to the land.

How many people go missing in the Australian Outback every year?

While official statistics vary, thousands of missing person reports are filed annually across Australia, with a small portion occurring in remote outback regions. Factors include harsh environmental conditions, remoteness, and travel accidents. Most cases are resolved quickly, but caution is advised in isolated areas.

What is the 10 year rule in Australia?

The “10-year rule” refers to aspects of Australian law where certain legal matters, such as property claims or immigration residency requirements, are influenced by a 10-year timeframe. Context varies by law; for example, some long-term residency or property statutes use a 10-year minimum period for rights or entitlements.

What is the biggest predator in Australia?

The largest terrestrial predator is the saltwater crocodile, found in northern Australia. On land, the dingo is the apex predator in much of the mainland outback. Other large predators include sharks in coastal waters, while snakes, spiders, and smaller predators contribute to the ecosystem.

How likely is it to see a snake in Australia?

Snakes are common in rural and outback areas, especially during warmer months. While sightings are possible, encounters with venomous snakes are rare if standard precautions are taken. Visitors should wear sturdy boots, avoid long grass, and remain alert when walking in bushland or around water sources.